My commentary on the state of play for Discrimination, Bullying and Sexual Harassment in the Medical Profession.

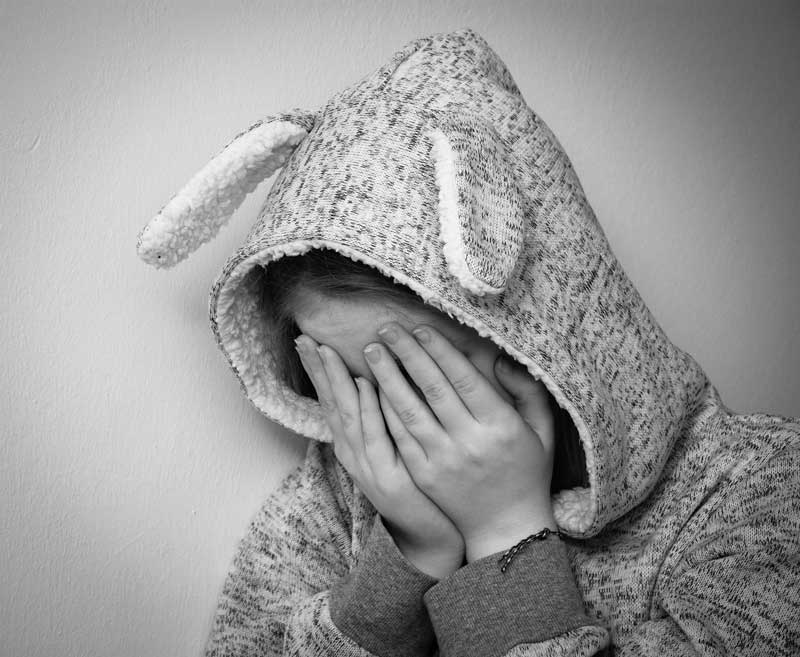

Part 2 – The dynamics of being a victim of bullying – Individual barriers to reporting

1. Many victims feel (or are made to feel) lucky to have a job at all. As such there is likely a cohort of doctors that are at greater risk of being victims of bullying: international medical graduates, those from a non-English speaking background.

There is also the concept of “fitting the mould” – those with outgoing personalities, a level of self-confidence, and emotional and physical resilience are likely advantaged with respect to career prospects.

2. Many victims fear jeopardising their career advancement, and with good reason. Despite the spotlight being focused on this issue over the last year, I have heard a narrative within the last few months of a junior doctor being told by a registrar: You need to lift your game. I know you don’t want to do Surgery, but we talk to each other and we can tell the Physicians that you’re no good.

3. In my experience, a significant amount of bullying is experienced between near-peers eg Principal House Officer (PHO/Non-training registrar) to Senior House Officer (SHO/post graduate year 3). The factors which drive this are likely:

- modelling their seniors (behavior/culture flow downwards),

- PHOs are stressed/overworked/under-experienced/under-supported/under-validated

- the concept of “kicking the cat” – when one is under pressure oneself, one will lash out upon someone lower down in the food chain, often to try to elevate oneself

4. Collectively, junior doctors often have the attitude that “The bullying issue is for senior doctors to sort out – it’s too big and complex for junior doctors”. This is likely true. It is more effective for one to fix a system from inside it rather from a position where one is trying to get into it.

A surgical trainee told me last year: “I can’t fix this – no junior doctor can. It needs to be fixed by the big people on the inside”

The following address by the President of the Australian Medical Students’ Association at the AMA National Conference last year articulated this powerfully:

facebook.com/LyndalPN/posts/10152872399564109

5. Within health organisations there tends to be unclear direction on how to act, how to make a complaint, and how the complainant will be protected. There exists procedures on how to make a complaint but I fear that even if a junior doctor knows about it, they will be highly unlikely to find it valuable or usable.

For a procedure to be effective, it must be robust, well promoted, and there must be investment by senior stakeholders to translate a complaint into safe and meaningful action. Junior (and senior) doctors must be able to trust that they will be protected, personally and professionally, and that a meaningful outcome will be achieved.

On a positive note, this tide may be starting to turn and I think that the stage is now set for significant improvements to occur in this arena within the medical profession. Junior doctors are garnering more courage to stand up for themselves and for each other.

An example of this was related by a medical student who attended the operating theatre during their rotation: An Intern was called to assist. When they arrived however, the surgeon said “I didn’t want you, I wanted the other one”. To their credit the Registrar defused the situation and responded with “We are all just trying to do our best to get the job done. Let’s keep going”. Sadly, this is not a robust response that may result in change in attitude or behavior, but it still took courage and it is a start.